A Test is Worth a Thousand Words

At $work, we run quite a few ML models in production, usually compiled using TensorRT.

While switching to a new major version, I encountered an unexpected problem. I got a failure in a test that feeds a video to a model expecting a specific classification, but the model produced complete garbage instead.

Having a test catch this regression was great1, but it left me at an impasse: what could I do besides opening an issue (beware, spoilers!) and hope for the best?

This led me on an unusual debugging quest, dissecting a Vision Transformer model layer by layer and even digging through torch internals.

Let’s set up a minimal (and failing) example, and then dive into debugging!

An Intro to Vision Transformers and TensorRT

Our goal is to take this short clip:

and run a video classification model on it, hopefully predicting that this is a video about making tea. Once we have that, we can compile the model and see if we get the same results.

A Vision Transformer, sometimes abbreviated to ViT, is a common architecture for modern image and video models. The specific model for which the test was failing is a video model based on the VideoMAE V2 paper and code.

We’ll go into (a lot) more detail later, but for now what you need to know is that it’s a model that accepts an input video (as an array of bitmap images) and outputs a classification (one of 710 labels, like riding a bike or roller skating).

Using torch for running inference on the GPU is probably the easiest option we have, but as we’ll see it isn’t always the fastest way to do so (which is expected, as torch has different design goals).

Instead, we can use TensorRT, which is a collection of a high-performance deep learning tools and libraries by NVIDIA.

There are a few ways to build TensorRT “engines” (compiled models ready to be loaded to the GPU for inference), but a common one is:

- Export the model to an ONNX file, which is sort of an intermediate representation of the model as a set of operators and weights.

- Use

trtexecto build an optimized engine from the ONNX file.

Hello ViT

Because VideoMAE has published checkpoints, we can actually do some inference right away (you can find the full code on GitHub at ohadravid/vit-trt).

We need a few dependencies:

uv init --name vit-trt --python 3.11

uv add "torch>=2.5.0" "pyav<14.0.0" "setuptools>=75.6.0" "timm>=1.0.12"

And then we can grab just two files from the VideoMAE repo: label_map_k710.txt and modeling_finetune.py (which we will rename to video_mae.py), and finally the vit_s_k710_dl_from_giant.pth checkpoint from huggingface.

After a little cleanup, we have something like this:

video_mae.py:

class Mlp(nn.Module):

...

class Attention(nn.Module):

...

...

class Block(nn.Module):

...

class VisionTransformer(nn.Module):

...

def vit_small_patch16_224(**kwargs) -> VisionTransformer:

model = VisionTransformer(

patch_size=16,

embed_dim=384,

depth=12,

num_heads=6,

mlp_ratio=4,

qkv_bias=True,

norm_layer=partial(nn.LayerNorm, eps=1e-6),

**kwargs)

return model

label_map_k710.txt:

riding a bike

marching

dodgeball

playing cymbals

checking tires

roller skating

...

First, we need to get a tensor of bitmaps from the video file.

from torchvision.io import read_video

video = read_video("tea.mp4", pts_unit="sec", output_format="TCHW")[0]

This results in a tensor with shape (Time, Channels, Height, Width).

Next, we are going to ensure our video fits the model’s expected input shape.

We’ll use torchvision.transforms.v2 to define a function that does that. You can check out the full code here, but the important thing is that we can use it like this:

transform = get_val_transform(image_wh=(224, 224), sequence_length=16)

# Before: video.shape == (127, 3, 1084, 870), video.dtype == torch.uint8

video = transform(video)

# After: video.shape == (16, 3, 224, 224), video.dtype == torch.float32

# Create an input batch of 6 videos (6, 16, 3, 224, 224)

video_as_batch = video.unsqueeze(0).repeat(6, 1, 1, 1, 1)

This will first resize our video to the expected 224x224 resolution, normalize it and then reduce it to the requested number of frames.

Now, we can create an instance of the model and load the checkpoint (the vit_small_patch16_224 function initializes the VisionTransformer class with all the correct parameters):

video_mae_model = vit_small_patch16_224(num_classes=710)

ckpt = torch.load("./vit_s_k710_dl_from_giant.pth", map_location="cpu", weights_only=True)["module"]

video_mae_model.load_state_dict(ckpt, strict=False)

Next, we’ll define our own model, which reshapes the input before calling the ViT:

class HelloViT(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, model: VisionTransformer):

super().__init__()

self.model = model

def forward(self, x):

B, T, C, H, W = x.shape

# The model expects (B, C, T, H, W),

x = x.permute(0, 2, 1, 3, 4)

cls = self.model(x)

cls = F.softmax(cls, dim=1)

return cls

model = HelloViT(video_mae_model)

Our model expects a batch of B videos, each with 16 frames. We then use permute to reorder the dimensions, and forward it.

Finally, we apply a softmax which is a standard way of converting the output into probabilities2.

Well, maybe “do some inference right away” was a bit of a stretch, but we’re nearly there!

All that’s left is to read the labels and call the model:

labels = Path("./label_map_k710.txt").read_text().splitlines()

device = torch.device("cuda") # or "mps" for MacOS's Metal, or "cpu".

model = model.to(device)

video_as_batch = video_as_batch.to(device)

cls = model(video_as_batch)

top_cls = torch.topk(cls[0], 3)

for cls_idx, score in zip(top_cls.indices, top_cls.values):

print(f"{labels[cls_idx]}: {score:.2f}")

This outputs:

making tea: 0.89

cooking egg: 0.01

setting table: 0.00

Success!

Hello ONNX and TensorRT

Now that we have a working model, we want to run this inference as fast as possible.

Using torch (model = model.eval(); with torch.inference_mode(): ...), on an L4 GPU we can do about 9 inference requests per second (See more in Appx. 1 - Performance).

But how much faster can we go?

First, let’s export the model to an ONNX file. This is as simple as:

uv add "onnx>=1.17.0" "onnxruntime>=1.17.1"

and:

onnx_bytes = io.BytesIO()

torch.onnx.export(

model,

(video_as_batch,),

onnx_bytes,

input_names=["video"],

output_names=["cls"],

)

Path("model.onnx").write_bytes(onnx_bytes.getvalue())

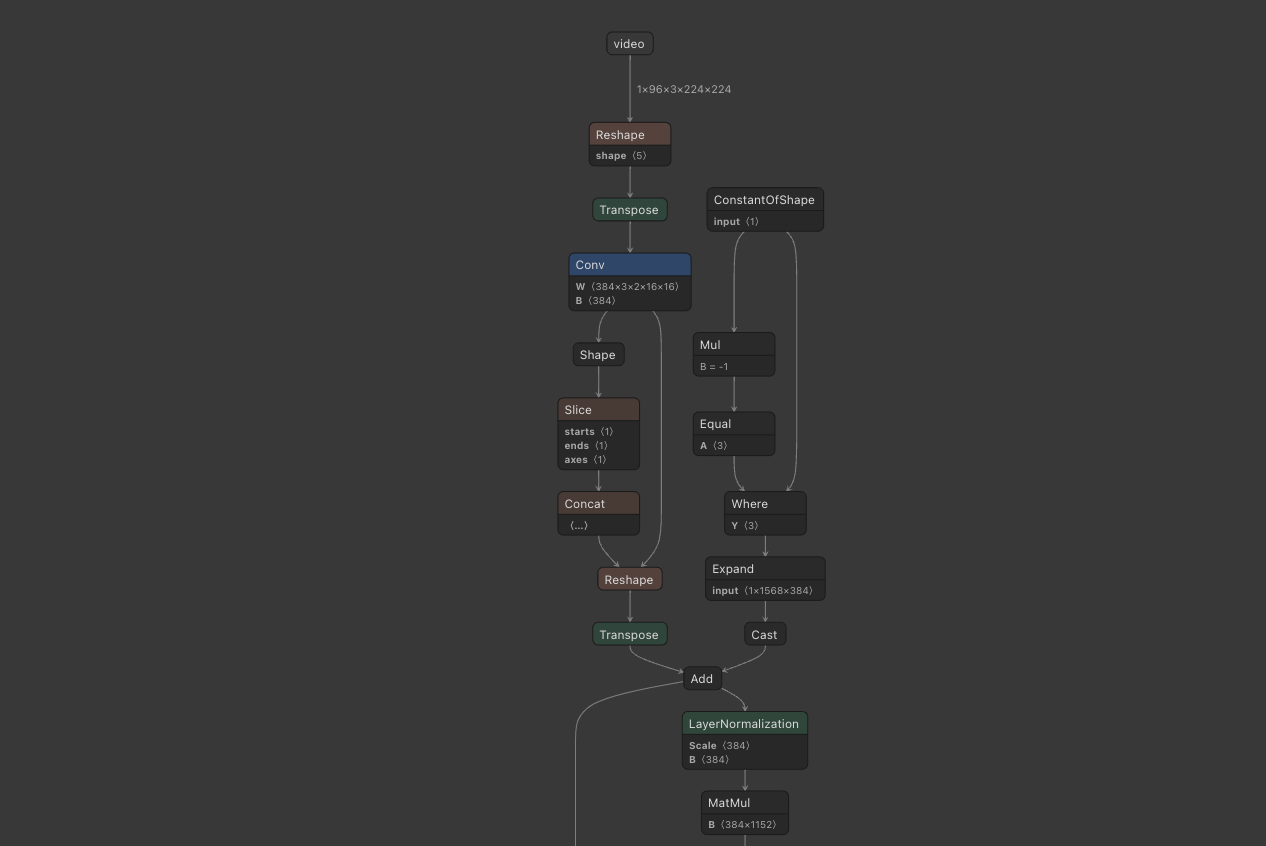

We can run inference with the resulting file or load it to Netron and see the the resulting compute graph:

Now we get to the fast part!

First, we’ll install torch-tensorrt:

uv add "torch-tensorrt>=2.5.0; sys_platform == 'linux'" "nvidia-modelopt[all]>=0.21.0; sys_platform == 'linux'"

Next, we’ll build the engine. Usually, we can do this directly in the shell using trtexec3, but we want to make sure we use matching versions with the Python env, so we’ll do it in the (slightly) harder way.

We’ll create a trt.Builder and load the ONNX file:

import tensorrt as trt

TRT_LOGGER = trt.Logger(trt.Logger.INFO)

builder = trt.Builder(TRT_LOGGER)

network = builder.create_network()

parser = trt.OnnxParser(network, TRT_LOGGER)

parser.parse(Path("model.onnx").read_bytes())

Then, we’ll set the fp16 flag, meaning we allow TensorRT to use half-precision layers (which are usually twice as fast) and build the engine.

config = builder.create_builder_config()

config.set_flag(trt.BuilderFlag.FP16)

config.builder_optimization_level = 3

engine = builder.build_serialized_network(network, config)

with open("model.trt", "wb") as f:

f.write(engine)

How much faster is the new engine? Well, we can run inference with the built engine using:

import torch_tensorrt

model = torch_tensorrt.runtime.PythonTorchTensorRTModule(

Path("model.trt").read_bytes(),

input_binding_names=[

"video",

],

output_binding_names=[

"cls",

],

)

cls = model(video_as_batch)

We can measure about 60 inference requests per second, or almost 7 times faster than plain torch. But did we get the correct result?

using remote controller (not gaming): 0.04

spray painting: 0.02

cleaning shoes: 0.01

We can try to turn off the FP16 flag and/or turn off optimizations entirely - but this still produces garbage.

And so, our adventure begins!

Binary Search is All You Need

Despite evidence to the contrary, it should be possible to compile a model with a standard architecture like ViT using TensorRT.

So what do we do now?

There’s one piece of advice that has never failed me. It goes like this:

How do you find a lion in the desert?

You cut the desert in half.

If the lion isn’t in the first half, it has to be in the second.

Keep dividing until there’s nowhere left for the lion to hide.

~ My dad, every time I got stuck debugging something

Essentially, it says that as long as you can bisect a problem into a working part and a non-working part, eventually you’ll have to arrive at the source of the issue (and presumably fix it).

Part 1

But how can we bisect this issue? We already know the problem is the TensorRT compilation step.

What if we can narrow down where in the model we start to see a difference between the outputs of torch and TensorRT? Then we might be able to change something in the model to avoid that.

What we can do is bisect along the model’s architecture: if we get matching data, we know the bug has to be in a more advanced layer, and if we get bad data we know it has to be somewhere in a previous layer.

Vision Transformer Architecture

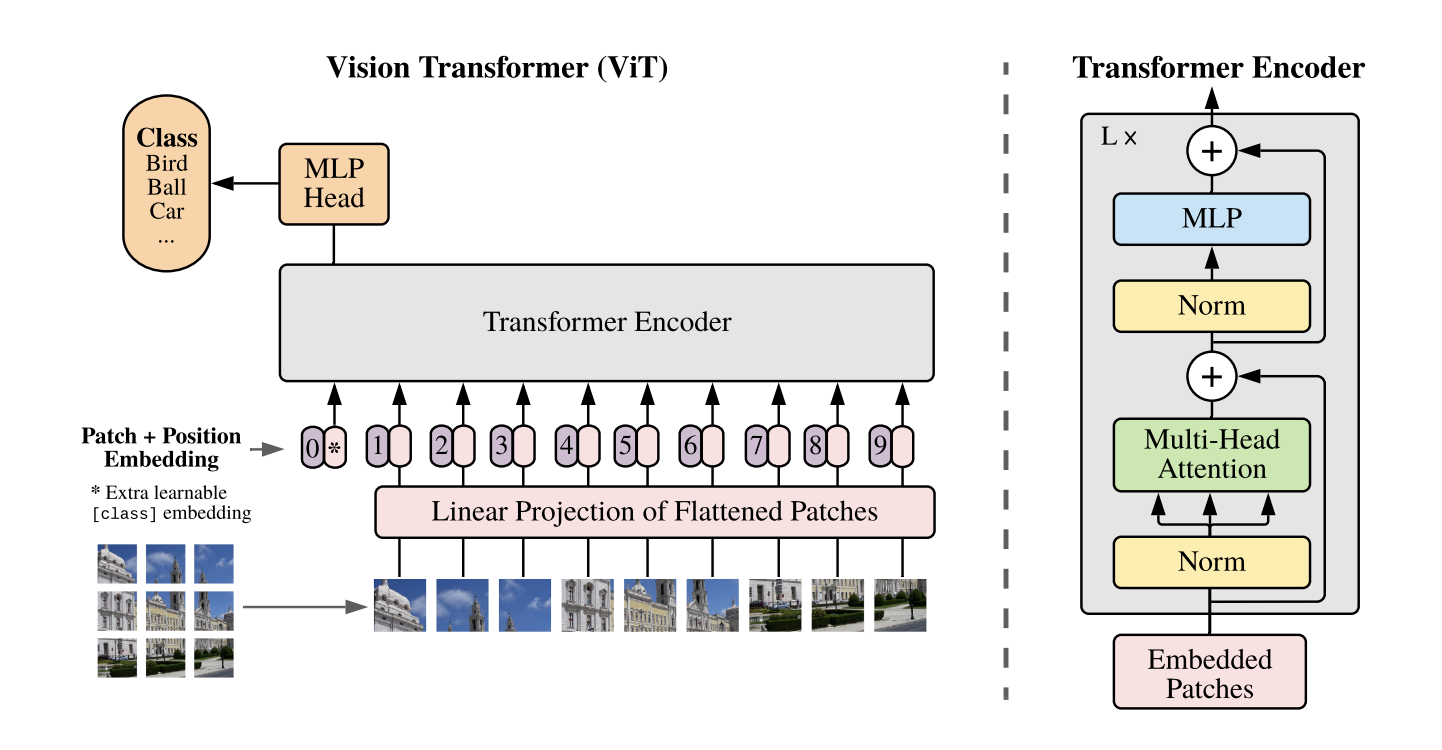

This is how the ViT architecture is presented in the original “An Image Is Worth 16x16 Words” paper:

A ViT, in high level:

- Takes an image (say 224x224 pixels), and splits it into patches (say of 16x16 pixels)

- Pass each of the patches through a convolution into an embedding (say 384 floats)4

- Pass the resulting patch-level embeddings (in our example, 14x14=196 embeddings of 384 floats) through some number of Transformer blocks

- Take the mean of all the embeddings and pass the result through a classification head (which is a linear layer that produces a single vector with length equal to the number of classes)

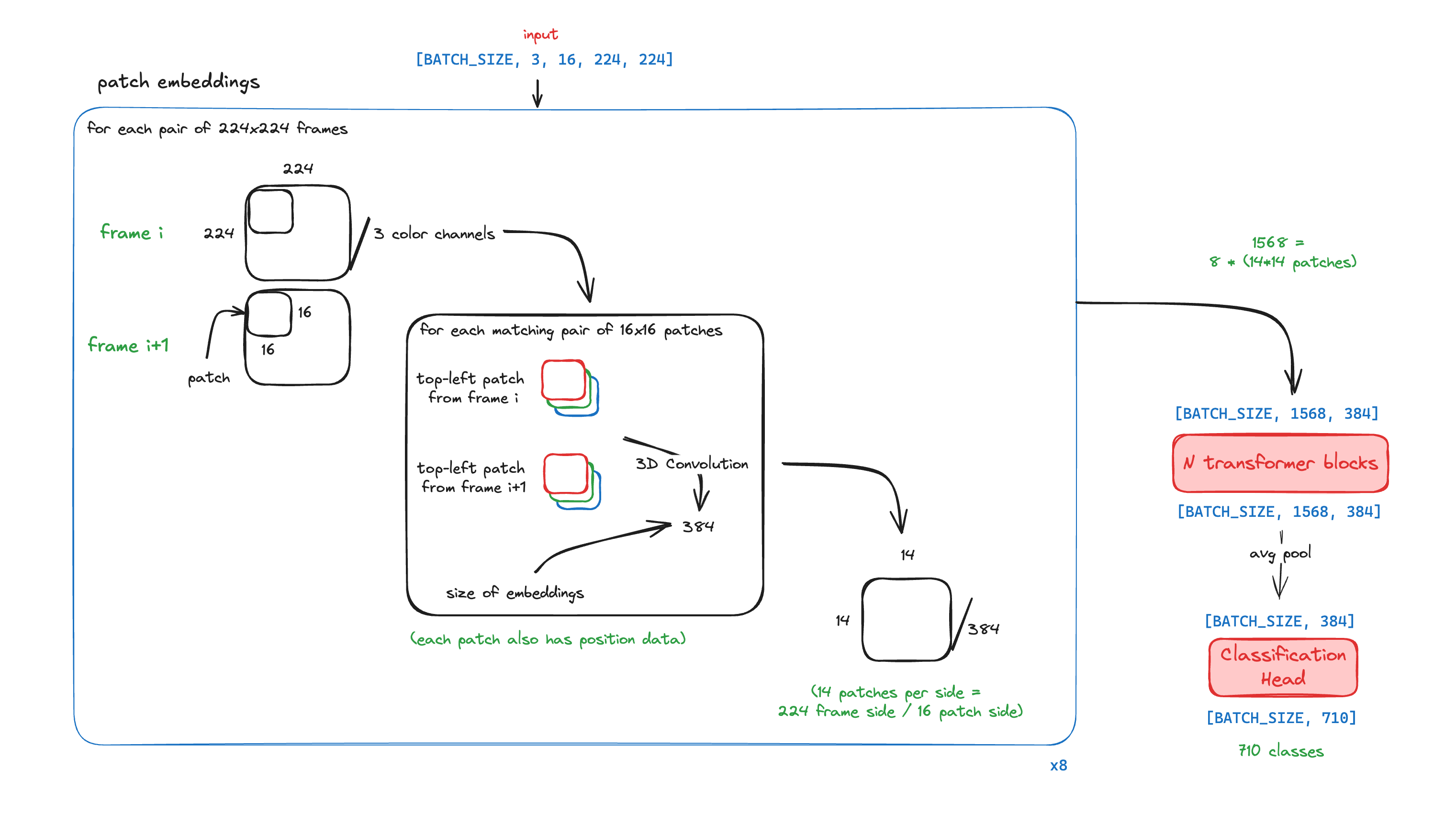

Because we work on videos, we want different images from the video to affect each other’s embeddings. Therefore, we don’t want to pass individual images to the Transformer blocks.

We could take all the patches from all the images and pass them to the Transformer blocks, but to save on compute we are actually going to combine each pair of consecutive frames, and generate a single patch embedding from each pair of matching patches - so for example, the top-left 16x16 patch from frame 0 will be combined with the top-left patch from frame 1 into a single, 384-length embedding.

Step 1

Our first bisect is going to be between the Transformer encoder (which is steps 1-3) and the classification head (step 4), since this is “the middle” (at least in terms of high-level parts).

Looking at the VisionTransformer module, we can see where we would like to inspect the data:

class VisionTransformer(nn.Module):

...

def forward(self, x):

x = self.forward_features(x)

x = self.head_dropout(x)

x = self.head(x)

return x

So, let’s do that! We’ll introduce a new output called dbg, and return it alongside x (the expected output).

class VisionTransformer(nn.Module):

...

def forward(self, x):

x = self.forward_features(x)

dbg = x

x = self.head_dropout(x)

x = self.head(x)

return x, dbg

We’ll need to update both the ONNX export and the TRT inference code, but only once.

-output_names=["cls"],

+output_names=["cls", "dbg"],

Then, we’ll print the dbg output (we’ll also change config.builder_optimization_level = 0 for faster builds).

$ uv run python main.py infer

Loading pretrained backbone from ./vit_s_k710_dl_from_giant.pth

Debug tensor shape: torch.Size([6, 384])

Debug tensor: tensor([[ 0.3958, 0.0676, 0.6927, ..., -0.5862, 0.7221, -0.6784],

[ 0.4127, -0.0593, 0.4587, ..., -0.5927, 0.4402, -0.4902],

[ 0.0011, 0.1264, 0.5177, ..., -0.4532, 0.0593, -0.1453],

[-0.0238, -0.1320, 0.4313, ..., -0.5991, 0.4598, -0.0770],

[ 0.2294, -0.1058, 0.4116, ..., -0.4042, 0.3858, -0.2119],

[ 0.4478, 0.0864, 0.4797, ..., -0.4002, 0.5532, 0.0147]],

device='cuda:0')

making tea: 0.89

cooking egg: 0.01

setting table: 0.00

$ uv run python main.py export_onnx && uv run python build_trt.py && uv run python main.py infer_trt

Converting ONNX to TRT: ./model.onnx -> ./model.trt

...

[12/26/2024-14:04:42] [TRT] [I] Engine generation completed in 11.5584 seconds.

[12/26/2024-14:04:42] [TRT] [I] [MemUsageStats] Peak memory usage of TRT CPU/GPU memory allocators: CPU 42 MiB, GPU 870 MiB

[12/26/2024-14:04:42] [TRT] [I] [MemUsageStats] Peak memory usage during Engine building and serialization: CPU: 4249 MiB

Debug tensor shape: torch.Size([6, 384])

Debug tensor: tensor([[ 0.5278, 0.2097, 0.4653, ..., -0.4175, 0.0789, -0.4231],

[ 0.2856, 0.0065, 0.8486, ..., -1.0791, 0.8267, -0.1802],

[ 0.1201, -0.3323, 0.7612, ..., -0.6855, -0.1262, -0.0579],

[ 0.2778, 0.0741, 0.7290, ..., -0.4290, 0.3762, -0.4922],

[-0.3330, 0.0882, 0.8950, ..., -0.5376, 0.4558, -0.3950],

[ 0.3596, -0.3323, 1.0605, ..., -0.9272, 0.5962, -0.3909]],

device='cuda:0')

using remote controller (not gaming): 0.04

spray painting: 0.02

cleaning shoes: 0.01

It helps to verify that the shape of the debug tensor is what we expect, and that we know how to interpret it.

In this case, a (6, 384) means we got 6 embedding vectors (one for every 16-frame video), each consisting of 384 floats.

We can see that the numbers don’t match at all, which means that the problem must occur somewhere in the Transformer encoder.

(You can also skip ahead to the final bisect)

Step 2

Let’s take a look at forward_features (edited a bit for clarity):

class VisionTransformer(nn.Module):

...

def forward_features(self, x):

x = self.patch_embed(x)

x = x + self.pos_embed

x = self.pos_drop(x)

for blk in self.blocks:

x = blk(x)

return self.fc_norm(x.mean(1))

This actually matches perfectly with the architecture schema we saw before.

Let’s see if we get the same patch-level embeddings. We’ll add a dbg = x after the patch_embed layer, and propagate it all the way out.

class VisionTransformer(nn.Module):

...

def forward_features(self, x):

x = self.patch_embed(x)

dbg = x

x = x + self.pos_embed

x = self.pos_drop(x)

for blk in self.blocks:

x = blk(x)

return self.fc_norm(x.mean(1)), dbg

def forward(self, x):

x, dbg = self.forward_features(x)

x = self.head_dropout(x)

x = self.head(x)

return x, dbg

And running it we get:

$ uv run python main.py infer

...

Debug tensor shape: torch.Size([6, 1568, 384])

Debug tensor: tensor([[[-2.6885e+00, -3.1712e+00, 3.9257e-01, ..., 4.6597e+00,

-1.2044e-01, -5.6132e-02],

[-3.0499e+00, -2.9882e+00, -5.4296e-01, ..., 6.3372e+00,

-1.1541e-01, 2.4910e+00],

...

$ uv run python main.py export_onnx && uv run python build_trt.py && uv run python main.py infer_trt

...

Debug tensor shape: torch.Size([6, 1568, 384])

Debug tensor: tensor([[[-2.6895e+00, -3.1719e+00, 3.9258e-01, ..., 4.6602e+00,

-1.2042e-01, -5.6122e-02],

[-3.0508e+00, -2.9883e+00, -5.4297e-01, ..., 6.3359e+00,

-1.1542e-01, 2.4902e+00],

...,

This time, the data matches! We see very small numerical differences5, but we don’t expect such minor deviations to derail the rest of the model.

The shape we get now is (6, 1568, 384), which is a batch of 6 different 16-frames videos, where each pair of 3x224x244 frames is split into 16x16 patches (since 224/16*224/16 == 196 patches per pair and 196*16/2 == 1568), with each patch projected into a 384-length embedding.

Step 3

Looking back at forward_features, the next step after the patch embeddings is the transformer blocks. Since all the blocks have the same inner layers, we can try to bisect by checking the features after the first transformer block.

class VisionTransformer(nn.Module):

...

def forward_features(self, x):

x = self.patch_embed(x)

x = x + self.pos_embed

x = self.pos_drop(x)

first_block_dbg = None

for blk in self.blocks:

x = blk(x)

if first_block_dbg is None:

first_block_dbg = x

return self.fc_norm(x.mean(1)), first_block_dbg

Running it again, we now get:

$ python main.py infer

...

Debug tensor shape: torch.Size([6, 1568, 384])

Debug tensor: tensor([[[-2.8630e-01, 1.0363e+00, 6.6786e-01, ..., -2.4567e-02,

2.9492e-01, 1.4561e+00],

[ 1.1604e+00, -4.3200e-01, -7.5475e-01, ..., 2.0366e+00,

-5.6720e-01, 3.7679e+00],

[-1.8967e-01, -4.0106e-01, -4.5669e-02, ..., 4.3814e-01,

-2.9767e-01, -1.4545e+00],

...,

$ uv run python main.py export_onnx && uv run python build_trt.py && uv run python main.py infer_trt

...

Debug tensor shape: torch.Size([6, 1568, 384])

Debug tensor: tensor([[[-4.9097e-01, 8.8086e-01, 6.8262e-01, ..., 3.1836e-01,

6.4307e-01, 1.3945e+00],

[ 1.0684e+00, -5.5322e-01, -7.6953e-01, ..., 2.3438e+00,

-2.6392e-01, 3.6562e+00],

[-1.8506e-01, -4.9512e-01, -7.0312e-02, ..., 6.3477e-01,

-1.0474e-01, -1.3789e+00],

...,

Seems like the Transformer block is where the miscompilation is.

Let’s keep digging!

Step 4

Looking at the implementation, we see

class Block(nn.Module):

...

def forward(self, x):

if self.gamma_1 is None:

x = x + self.drop_path(self.attn(self.norm1(x)))

x = x + self.drop_path(self.mlp(self.norm2(x)))

else:

x = x + self.drop_path(self.gamma_1 * self.attn(self.norm1(x)))

x = x + self.drop_path(self.gamma_2 * self.mlp(self.norm2(x)))

return x

Bisecting here means checking the value between the Attention layer (self.attn) and the MLP layer (self.mlp).

class Block(nn.Module):

...

def forward(self, x):

if self.gamma_1 is None:

x = x + self.drop_path(self.attn(self.norm1(x)))

dbg = x

x = x + self.drop_path(self.mlp(self.norm2(x)))

else:

x = x + self.drop_path(self.gamma_1 * self.attn(self.norm1(x)))

dbg = x

x = x + self.drop_path(self.gamma_2 * self.mlp(self.norm2(x)))

return x, dbg

And once more:

```bash

$ uv run python main.py infer

...

Debug tensor shape: torch.Size([6, 1568, 384])

Debug tensor: tensor([[[-0.3382, -0.2649, 1.9496, ..., 3.7920, 0.1358, 1.0158],

[ 0.3417, -0.4437, 1.9564, ..., 4.6808, 0.0553, 3.2606],

[-0.1016, -1.7795, 1.7658, ..., 3.8132, 0.1236, -1.4414],

...,

$ uv run python main.py export_onnx && uv run python build_trt.py && uv run python main.py infer_trt

...

Debug tensor shape: torch.Size([6, 1568, 384])

Debug tensor: tensor([[[-0.3926, -0.1250, 1.8721, ..., 3.9922, 0.1176, 0.9531],

[ 0.4844, -0.2109, 2.1133, ..., 4.3984, -0.0686, 3.1055],

[-0.2363, -1.7500, 1.7930, ..., 4.1016, 0.1726, -1.3770],

...,

Seems like the problem is in the attention layer!

Step 5

This is how the attention layer is defined:

class Attention(nn.Module):

...

def forward(self, x):

B, N, C = x.shape

qkv_bias = None

...

qkv = F.linear(input=x, weight=self.qkv.weight, bias=qkv_bias)

qkv = qkv.reshape(B, N, 3, self.num_heads, -1).permute(2, 0, 3, 1, 4)

q, k, v = qkv.unbind(0)

x = F.scaled_dot_product_attention(

q,

k,

v,

dropout_p=self.attn_drop.p if self.training else 0.0,

scale=self.scale,

)

x = x.transpose(1, 2).reshape(B, N, -1)

x = self.proj(x)

x = self.proj_drop(x)

return x

And if we continue to bisect we’ll find out that we get matching data before F.scaled_dot_product_attention, and non-matching data after it. We found where the problem is! But what can we do about it?

Part 2

It’s time for a confession:

The original VideoMAE code doesn’t use the F.scaled_dot_product_attention function at all!

They use the explicit formulation from the “Attention Is All You Need” paper:

$$ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{Q K^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right) V $$

Which looks like this in torch:

q = q * self.scale

attn = (q @ k.transpose(-2, -1))

attn = attn.softmax(dim=-1)

x = (attn @ v)

We actually introduced F.scaled_dot_product_attention during the cleanup.

But why did we do this? (Please bear in mind that the cleanup happened about a year before the issue appeared).

Well, F.scaled_dot_product_attention is a lot faster because it can use fused kernels to do the attention operation, like FlashAttention-2.

On my machine (Using an L4 GPU) it’s about 50% faster than the explicit formulation, which is important for training and developing the model (Again, see more in Appx. 1 - Performance).

# Using `F.scaled_dot_product_attention`

$ uv run python ./main.py infer

Loading pretrained backbone from ./vit_s_k710_dl_from_giant.pth

Inference runs per sec: 9.78 on cuda

making tea: 0.89

cooking egg: 0.01

setting table: 0.00

# Using explicit Attention

$ uv run python ./main.py infer

Loading pretrained backbone from ./vit_s_k710_dl_from_giant.pth

Inference runs per sec: 6.00 on cuda

making tea: 0.89

cooking egg: 0.01

setting table: 0.00

What will happen if we try to export the explicit-attention model and build an engine?

$ uv run python main.py export_onnx && uv run python build_trt.py && uv run python main.py infer_trt

Loading pretrained backbone from ./vit_s_k710_dl_from_giant.pth

...

Inference runs per sec: 62.22 on cuda

making tea: 0.89

cooking egg: 0.01

setting table: 0.00

Hurray! We lost some performance when running with torch, but at least we get a working engine now (both engines will have similar performance since TensorRT can optimize both versions).

But what’s different about the explicit version? And can we get back the performance we lost? Let’s do a quick recap, and then explore these questions.

Summary

We covered a lot of ground: How to run inference on a ViT-based model, How to export to ONNX and use TensorRT compilation, and finally how to print-debug an ML model.

Finding the place along the model’s architecture where the original and compiled model start to diverge allowed us to change the implementation to avoid triggering the bug.

This really highlights how powerful debugging by bisecting a problem can be: having to do O(logN) steps (such as editing the model and recompiling) almost always converges quickly enough on the problem.

We also saw that while it is magic/math that makes the models work, the actual code and tools behind them are not magical at all, and can be inspected, edited and modified just like any other piece of software.

However… we ended up using a “worse” version of the attention layer, and we don’t even know what’s different about it that makes it work correctly.

It would be nice if we can keep the performance we had before and still produce working engines, wouldn’t it?

Going Deeper

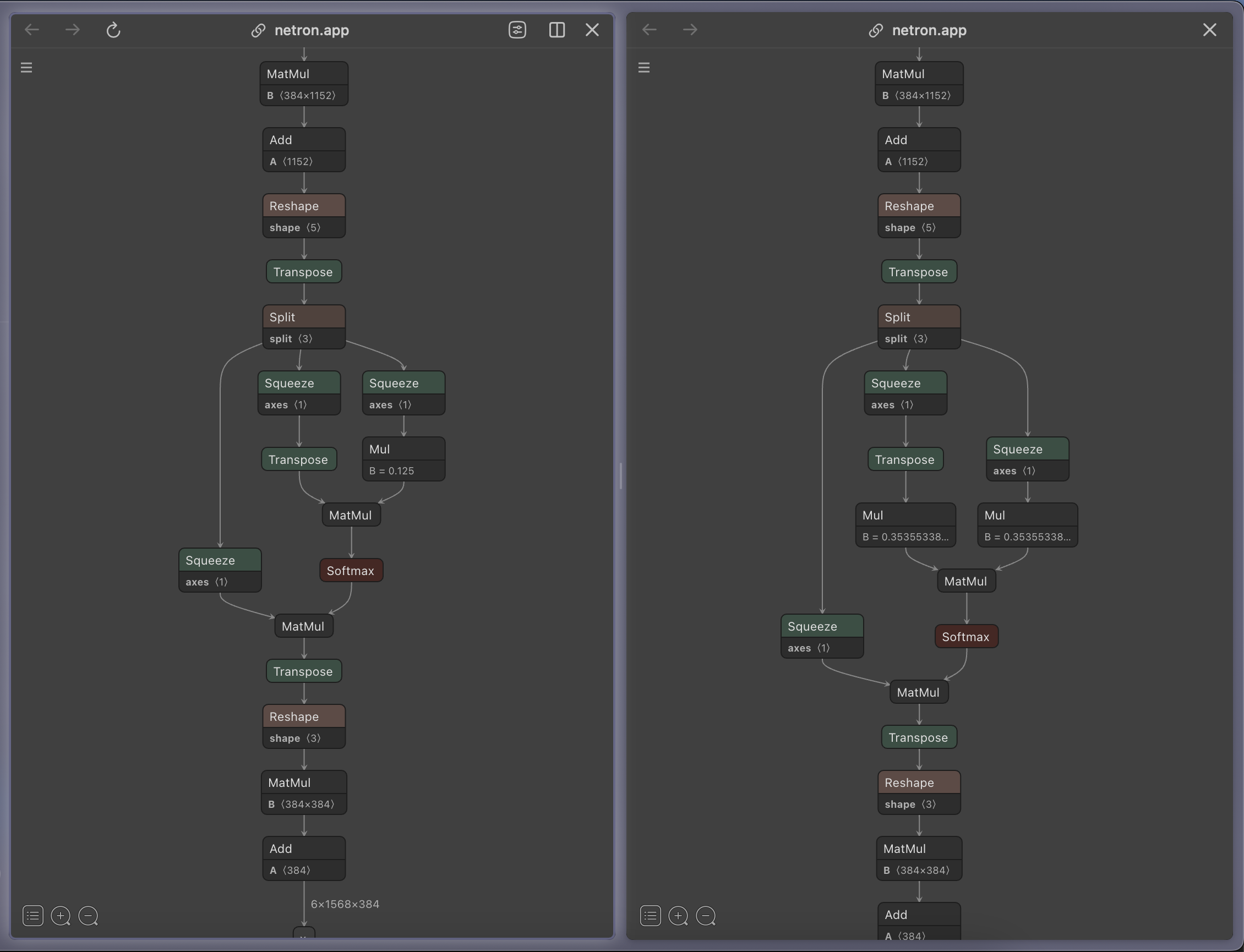

The first thing we can do is export only the attention layers to ONNX and try to compare them.

x = torch.zeros((6, 1568, 384))

attn = model.model.blocks[0].attn

onnx_bytes = io.BytesIO()

torch.onnx.export(

attn,

(x,),

onnx_bytes,

input_names=["x"],

output_names=["x"],

)

Path("attn.onnx").write_bytes(onnx_bytes.getvalue())

Using Netron again, the only difference between the explicit version (left) and the scaled dot product version (right) seems to be that the Mul B = 0.125 in the middle was split into two Muls (each of B = sqrt(0.125) = 0.353..).

This seems to trigger a bug in the TensorRT compiler (see the issue on GitHub), but doesn’t tell us much beyond that.

As a side note, while reviewing an earlier version of this article izikgo pointed me to this PR, which seems to explain why F.scaled_dot_product splits the multiplication factor like this - it is actually more numerically stable.

Reading the documentation, one way to do this is to check if we are exporting an ONNX and only use the explicit version then, but that seems so ugly! There must be a better way.

if torch.onnx.is_in_onnx_export():

attn = (q @ k.transpose(-2, -1))

...

else:

x = F.scaled_dot_product_attention(...)

Reading some more, there’s also a function called F.multi_head_attention_forward.

If you really want to, you can see how the full 19-parameter-call looks like here. It produces a working engine (and a slightly different ONNX) but unfortunately it’s even slower than the explicit version!

But why? And can we do better?

torch usually provides two versions of each operation: a functional one and a module-based one (e.g., torch.nn.functional.conv1d and torch.nn.Conv1d).

For attention, the module-based version is nn.MultiheadAttention. Reading the code in torch/nn/modules/activation.py,

we can see that there is a fast_path that uses torch._native_multi_head_attention when it can, and only calls the slower F.multi_head_attention_forward when that’s not possible.

This means that if we use nn.MultiheadAttention, we’ll presumably get back the performance we lost (and probably an ONNX that doesn’t trigger the bug).

This is well and good, but if we replace our custom attention layer, we won’t be able to load our existing weights.

Fortunately, we are not the first ones to run into just this problem, and there’s a neat trick to add backward compatibility for our existing weights.

First, we’ll inherit from nn.MultiheadAttention and add a _version = 2 field to the class.

class AttentionUsingMHA(nn.MultiheadAttention):

_version = 2

def __init__(self,

dim,

num_heads=8,

qkv_bias=False,

qk_scale=None,

attn_drop=0.,

proj_drop=0.,

attn_head_dim=None):

assert qk_scale is None or qk_scale is True, f"qk_scale is not supported in this class, got {qk_scale}"

assert attn_head_dim is None, f"attn_head_dim is not supported in this class, got {attn_head_dim}"

assert proj_drop == attn_drop, f"proj_drop must be equal to attn_drop, got {proj_drop} and {attn_drop}"

super().__init__(embed_dim=dim, num_heads=num_heads, dropout=attn_drop, bias=qkv_bias, add_bias_kv=False, batch_first=True)

Next, we’ll overload _load_from_state_dict. Whenever we get state from the older version, we’ll remap the keys and adjust the shapes to what nn.MultiheadAttention expects.

class AttentionUsingMHA(nn.MultiheadAttention):

...

def _load_from_state_dict(

self,

state_dict,

prefix,

local_metadata,

strict,

missing_keys,

unexpected_keys,

error_msgs,

):

version = local_metadata.get("version", None)

if version is None or version < 2:

# The old layer uses `q_bias` and `v_bias` to construct `qkv_bias`.

q_bias = state_dict.pop(f"{prefix}q_bias")

v_bias = state_dict.pop(f"{prefix}v_bias")

if q_bias is not None:

qkv_bias = torch.cat(

(q_bias, torch.zeros_like(v_bias, requires_grad=False), v_bias)

)

state_dict[f"{prefix}in_proj_bias"] = qkv_bias

key_mapping = {

"qkv.weight": "in_proj_weight",

"proj.weight": "out_proj.weight",

"proj.bias": "out_proj.bias",

}

# .. Rename the keys f"{prefix}{from_key}" -> f"{prefix}{to_key}" ..

And finally, we’ll overload forward to keep the existing arguments and return values.

class AttentionUsingMHA(nn.MultiheadAttention):

...

def forward(self, x):

attn_output, attn_output_weights = super().forward(query=x, key=x, value=x)

return attn_output

You can see the full implementation here.

Using this new implementation (by setting Attention = AttentionUsingMHA in video_mae.py), we get back our lost performance while still producing an ONNX which doesn’t trigger the bug.

$ # Using `AttentionUsingMHA`

$ uv run python ./main.py infer

Loading pretrained backbone from ./vit_s_k710_dl_from_giant.pth

Inference runs per sec: 9.70 on cuda

making tea: 0.89

cooking egg: 0.01

setting table: 0.00

$ uv run python main.py export_onnx && uv run python build_trt.py && uv run python main.py infer_trt

...

making tea: 0.89

cooking egg: 0.01

setting table: 0.00

Phew!

Special thanks to Omer, Izik, Yuval and Yoav for reviewing earlier drafts of this article.

Edit 1: NVIDIA also has a tool called Polygraphy, which (among other things) can be used to auto-bisect failing ONN models.

Appendixes

Appendix 1 - Performance

(Run)time is an illusion, lunchtime doubly so.

Measuring the runtime performance of a model can almost never be done “in a vacuum”.

We are measuring a mix of library performance, hardware capabilities and load, compiler optimizations, communication overhead, and the actual architecture of the model.

We also might want to improve the performance of the training step, which also includes backprop calculation.

However, being imprecise is not an excuse not to measure something, but please be aware that there are even more asterisks than usual for the numbers I’m sharing here.

First and foremost: we are measuring a (relatively) small model (vis_s is the small variant and has 22M parameters, vit_b is the base variant which has 86M parameters),

which means that the overhead of CPU<->GPU communication will have a bigger effect on our measurements.

I’ll touch on batching in the end, but we will be using a batch size of 6 videos. Smaller batch sizes can leave the GPU underutilized, depending on the model architecture and data.

We are going to measure the throughput by noting the Inference Runs per Second.

I’m using a g2-standard-96 machine in GCP which has a single NVIDIA L4 GPU, and a MacBook Pro with the M3 Pro chip.

I measured everything using torch == 2.5.1 and torch-tensorrt == 2.5.0 which uses TensorRT 10.3.0.

Checking with different TensorRT versions can be done using docker and NVIDIA’s pytorch images:

$ docker run --gpus all --rm -it -v $(pwd):/code -w /code nvcr.io/nvidia/pytorch:24.12-py3 bash

$ root@cd60802e9604:/code# pip install "onnxruntime>=1.17.1" "pyav<14.0.0" "timm>=1.0.12"

$ root@cd60802e9604:/code# python ./main.py export_onnx && python ./build_trt.py && python ./main.py infer_trt

First, for our “baseline” we will compare the 4 attention versions, which are:

- Explicit -

x = (attn @ v).transpose(1, 2) - Scaled-dot-product -

x = F.scaled_dot_product_attention(q, k, v, ...) - Functional MHA -

x = F.multi_head_attention_forward(x, x, x, ...) - Layered MHA - Inheriting from

nn.MultiheadAttention

As we saw before, Scaled-dot-product and Layered MHA are the fastest, followed by Explicit and last (But not least, certainly not in terms of the number of arguments) is Functional MHA.

The first optimization we can use is to set the precision of float32 matrix multiplications using torch.set_float32_matmul_precision('medium'), which gives all of them about a 50% jump in performance.

We can also use model = model.half(), which will use half precision (fp16) in torch (similarly to what we did in TensorRT).

Torch also supports using model = torch.compile(model), which can help improve the performance even more.

As expected, the half configuration is about 2x faster than the fp32 version, with torch.compile giving us another boost of about 20%.

| Configuration | Explicit | Scaled-dot-product | Functional MHA | Layered MHA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torch Baseline | 6.00 | 9.78 | 5.66 | 9.70 |

| Torch with fp32 Medium Precision | 8.86 | 13.89 | 6.74 | 13.84 |

| Torch with fp16 Precision | 13.23 | 37.00 | 21.44 | 37.23 |

Torch with fp16 Precision and compile | 18.28 | 45.75 | 26.56 | 44.40 |

And we didn’t even talk about quantization!

We can also compare this to other platforms and architectures (all using the Layered MHA).

| Platform / Configuration | Inference Runs per Sec |

|---|---|

| TensorRT (fp16) | 57.31 |

Torch with CUDA (fp16 and compile) | 44.40 |

| TensorRT (fp32) | 8.5 |

| Torch with CUDA (fp32 Medium Precision) | 13.84 |

| Torch with Metal (fp32) | 2.20 |

| Torch with Metal (fp16) | 3.15 |

| Torch with CPU | 0.32 |

On macOS, the Explicit version is actually slightly faster than the Layered MHA one.

Appendix 2 - Batching

While our current batch size is 6, we can quickly measure throughput for different batch sizes using trtexec.

First, we’ll need to export an ONNX with a dynamic batch size by passing dynamic_axes to torch.onnx.export:

torch.onnx.export(

model,

(video_as_batch,),

onnx_bytes,

dynamic_axes={

"video": {0: "B"},

"cls": {0: "B"},

},

)

Then, we can try setting the batch size to different values and observe the results:

$ trtexec --onnx=./model.onnx --fp16 --optShapes=video:1x16x3x224x224 --minShapes=video:1x16x3x224x224 --saveEngine=./model_exec.trt

...

[12/31/2024-06:18:45] [I] TensorRT version: 10.5.0

12/31/2024-06:18:45] [I] Selected Device: NVIDIA L4

..

[12/31/2024-06:19:40] [I] === Performance summary ===

[12/31/2024-06:19:40] [I] Throughput: 308.748 qps

$ trtexec --onnx=./model.onnx --fp16 --optShapes=video:2x16x3x224x224 --minShapes=video:1x16x3x224x224 --saveEngine=./model_exec.trt

...

[12/31/2024-20:02:03] [I] Throughput: 179.218 qps

$ trtexec --onnx=./model.onnx --fp16 --optShapes=video:4x16x3x224x224 --minShapes=video:1x16x3x224x224 --saveEngine=./model_exec.trt

...

[12/31/2024-20:03:46] [I] Throughput: 83.2834 qps

$ trtexec --onnx=./model.onnx --fp16 --optShapes=video:6x16x3x224x224 --minShapes=video:1x16x3x224x224 --saveEngine=./model_exec.trt

...

[12/31/2024-20:03:46] [I] Throughput: 55.1338 qps

$ trtexec --onnx=./model.onnx --fp16 --optShapes=video:8x16x3x224x224 --minShapes=video:1x16x3x224x224 --saveEngine=./model_exec.trt

...

[12/31/2024-20:03:46] [I] Throughput: 39.536 qps

Appendix 3 - You can’t possibly mean() that

The model I’m presenting here (HelloViT) is simplified and it might not actually be a good idea to use a ViT exactly like this.

I’ll point out two important things:

- By diluting the video like this, the model is getting “mismatched” positional embeddings - which means consecutive frames are actually farther apart in time than they should be (and the same goes for very short videos).

- If we wanted to support longer videos, we could try to take the

meanof the frame-level embeddings of the entire video, normalize and only then run the classification head.

and probably saved me from writing an entire article about tests (for now). ↩︎

Why isn’t it part of the ViT already? Well, because

log_softmaxis better for gradient calculation. Since we aren’t training this model, we don’t really care about gradients and back propagation. ↩︎This script is equivalent to running:

trtexec --onnx=./model.onnx --fp16 --saveEngine=./model.trt↩︎A positional embedding is also added to each patch embedding (which is just a calculated value to describe where in the grid of

224/16x224/16=14x14the patch is). ↩︎There are two sources of numerical differences: we are using fp32 in

torchand fp16 in the built engine, and TensorRT is allowed to fuse operations which in the general case does not have to preserve the result bit for bit. Because we have “nice” data (normalized inputs, normalized layers, etc), we can dismiss very small differences relatively safely. ↩︎